Correcting Overcorrection

fall 2022

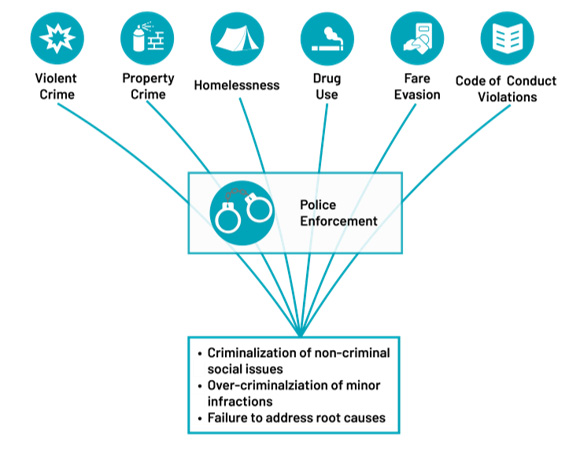

Police have a constant presence on mass transit, but to what end exactly? In 2020, just 2% of crime in New York City occurred on the subway, and yet 10% of the NYPD was tasked with patrolling stations and train cars. Then, in April 2022, the department announced that arrests on the subway increased 64% from April 2021, with a 51% increase in typically nonviolent fare evasion offenses. From October 2017 to June 2019, 90% of fare-related arrests were of Black and brown people. Policing on mass transit, though essential, has led to racial discrimination and unnecessary aggression toward nonviolent crimes not just in New York, but across the U.S.

Beyond that, over-policing has also altered public perception. A wary public has been slow to return to mass transit after the pandemic, which in turn makes the transit systems less money to invest back into improving rider experience. “The public doesn’t feel safe when police are on the platform pinning teenagers to the floor,” says designer James Zhang. “You want the public to feel safe and to support each other, which includes people who are struggling or living in your transit system. It’s just the right thing to do.”

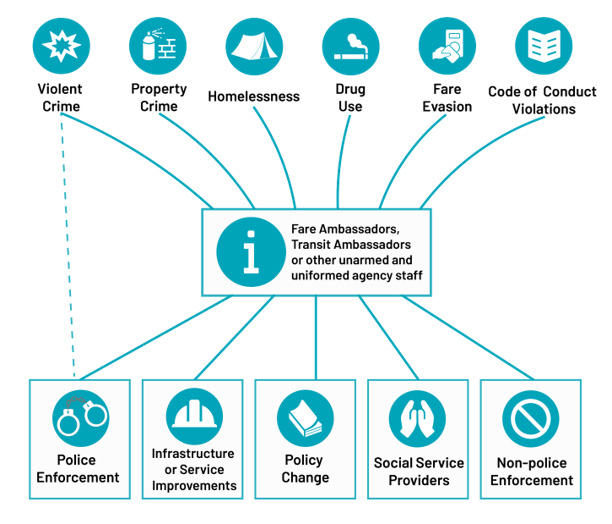

Zhang, who grew up in New York before moving to Atlanta, realized he wasn’t alone in his thinking when a former colleague out of Chicago posted an article on social media about the city’s use of K9 units in transit systems, a long-questioned practice with often violent results. Also alarmed by the post was Ashankh Jaishankar, a Seattle-based designer. He and Zhang connected virtually and committed to discovering and sharing a series of well-researched guidelines for alternatives and improvements to policing on mass transit. “We wanted to find a series of solutions for cities to try out, so they could see which works best for them,” says Jaishankar. “That’s how you gradually transition away from investing more into the current status quo.”

The duo then went on the hunt for transit professionals around the U.S. who would be excited to talk to them about their outreach programs. Professionals from Seattle, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Portland, Las Vegas, and Denver volunteered to participate. One common thread that emerged from their interviews was that each of these cities’ transit agencies had been struggling with the financial burden of hiring police officers. For these agencies, finding alternatives to traditional policing served as both a social good and a cost-saving measure.

Different cities found different solutions. Philadelphia paired police officers with mental health specialists (known as the co-responder model) on trains and in stations while also establishing Hub of Hope, which assists homeless people in finding housing; access to physical and behavioral health resources; and simple meals, laundry services, and restroom facilities (in 2022, they served over 28,000 meals and helped more than 2,500 individuals move into more stable housing). Portland, meanwhile, decriminalized fare evasion and drug use, implemented a low-income fare program at a 72% discount, and increased unarmed security. San Francisco also implemented the co-responder model. In addition, the city hired previously incarcerated people for an elevator attendant program that greatly reduced public urination and, by proxy, elevator maintenance while increasing customer satisfaction 95%. “Sometimes just having a friendly presence in the system instead of an armed presence makes a world of difference,” Jaishankar adds.

Now, their findings form a report that will inform transit professionals in other cities about proven policing alternatives. They also presented their findings at the American Public Transportation Association’s Mobility Conference in April 2023, and Zhang and Jaishankar hope to publish their study as a peer-reviewed journal article in the future. “Simply from a health standpoint, you can’t police your way out of every situation on the subway,” Zhang says. “Luckily, a lot of transit agencies have recognized that and made changes, and they can be exemplars for other cities.”

More Stories