Womxn of Action

fall 2022

Toronto-based designers Eunice Wong and Vinaya Mani had often discussed equity in design, the biases they saw in urban planning decisions, and the far-ranging implications of those decisions. But even they were taken aback by an article from researcher Gerben Helleman that investigated why girls play outside less than boys. “Parks simply are not programmed well enough that everyone finds them comfortable, and so the number of girls who go to playgrounds after the age of nine drastically drops,” Mani explains. “But it’s not just parks, it’s everywhere. And to change that, we need to push ourselves to be more vocal about it.”

Motivated by a desire to improve equity in the public realm, they set out to define a series of guidelines for how urban spaces can be designed to be more inclusive. Wanting to extend their research beyond parks, they first defined the myriad ways public spaces are designed without taking womxn into account. “Issues of safety and comfort certainly don’t just affect cisgender women,” Wong says. They included challenges like the width of sidewalks, the proximity of streetlights to garbage cans and benches, and the testing of wind tunnels’ effect on the typical able-bodied male figure versus the female one.

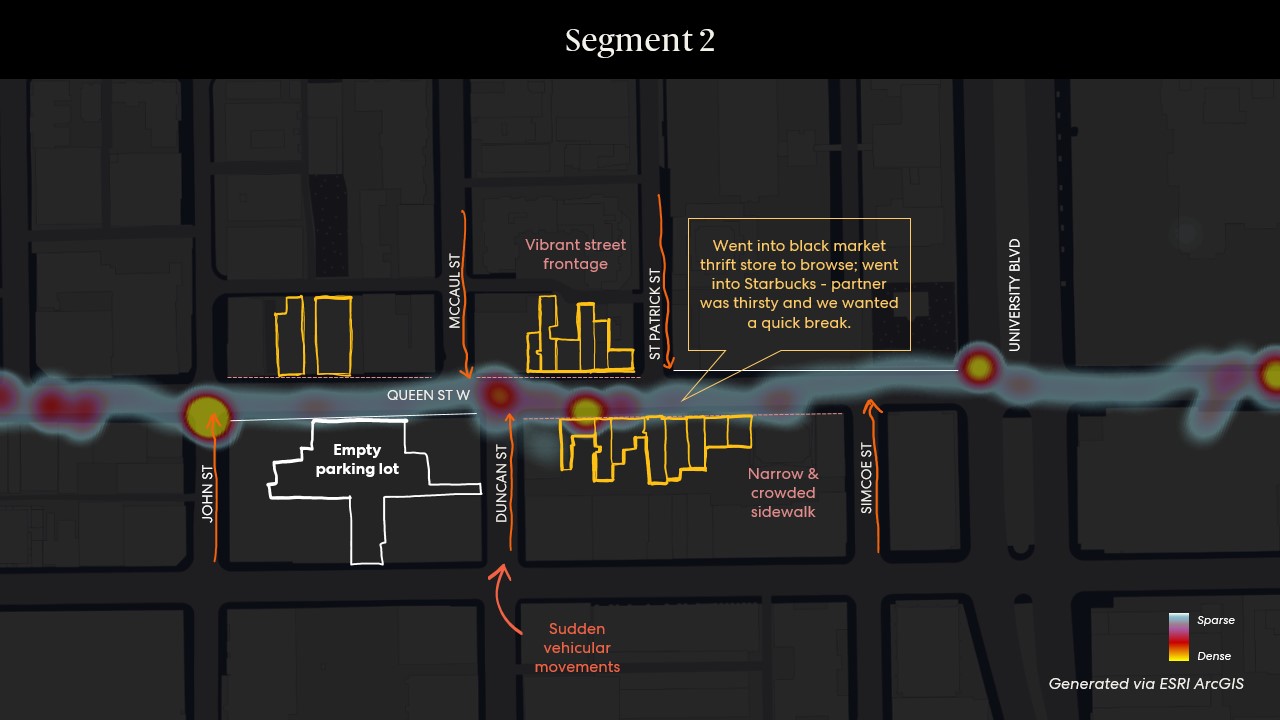

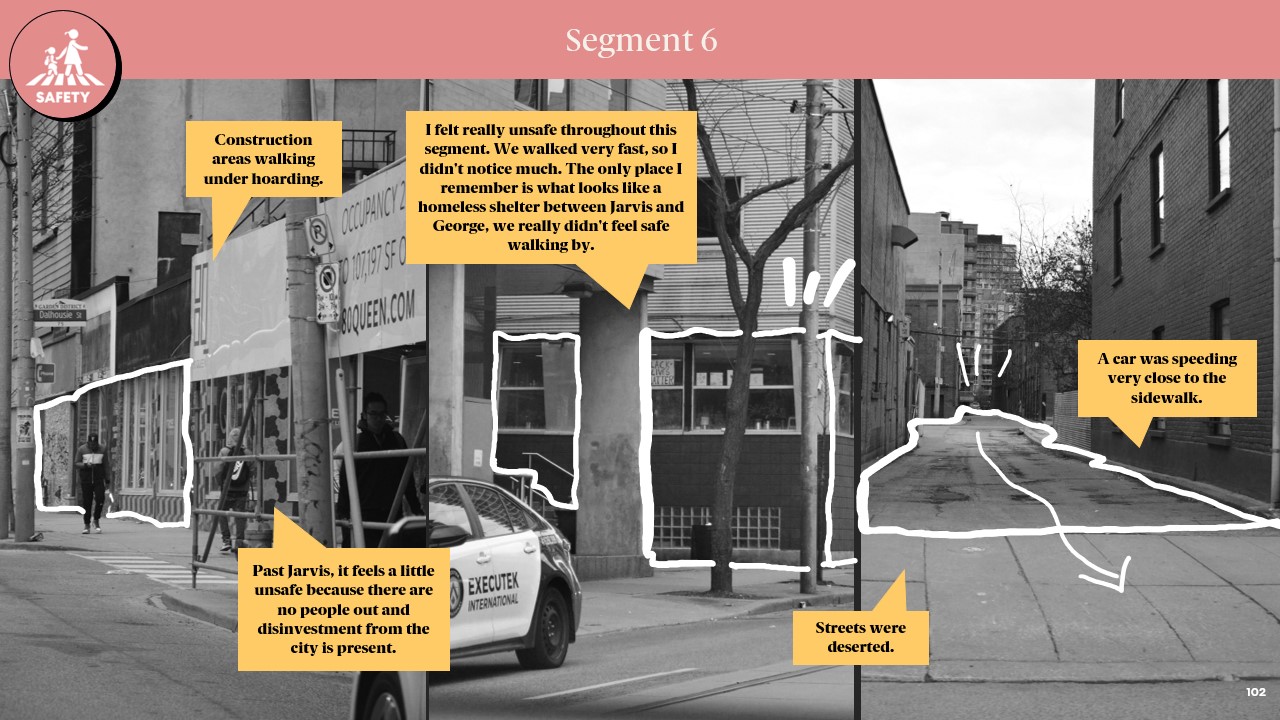

Unable to find reliable or consistent external data in their research, Wong and Mani set out to conduct their own experiment. They recruited 20 people ranging in age from 19 to 65, 19 of whom identified as female and one of whom identified as female/non-binary/gender non-conforming. Participants were asked to walk a certain route throughout Toronto, which they tracked through Strava—an app that uses GPS to record physical exercise like running, walking, or biking—between 8:00am and 7:00pm over the course of a few weeks. During each walk, participants answered a series of questions about their comfort level and recorded any environments that made them feel safe, unsafe, or that impacted their general enjoyment.

“If you design something for vulnerable populations, you end up designing something for everyone.”

― WONG

Wong and Mani divided the routes into a variety of urban typologies found in Toronto (while keeping these details from participants to mitigate any potential bias): the main retail strip, an area with a high concentration of restaurants and cannabis stores, the civic strip, the mall and its surroundings, the hospital area, and the garden strip.

Their findings, consolidated into a 122-page booklet titled “Confronting the Sexist City,” suggest that there is room for improvement across the city. For example, 85% of participants noted that an abundance of construction made them feel less safe in the mall area, as alternative pathways around buildings often aren’t lit as well as the street and force pedestrians into narrower walking paths. Another significant finding transcended all routes: Participants felt safer in areas where more people were on the street, while vacant storefronts and empty parks made them feel less safe

Beyond simply documenting problem areas, the guide suggests inclusive design strategies. One such solution they call “The Gift of Choice,” which ensures areas are designed so pedestrians can cross the street or enter a building or store whenever they might need to avoid a conflict or seek help. As for construction sites, specifically, Wong and Mani suggest more adequate signage, better lighting, and higher quality pathways as solutions when construction disrupts the flow of the area. “This guide can be a 101 on how to be more aware of typical city standards and guidelines that discriminate or are built against our demographic,” Wong says.

The designers acknowledge, however, that implementing their recommendations won’t completely erase sexism. But creating spaces that help womxn feel safer and more comfortable will ultimately benefit the broader community, too. “If you design something for vulnerable populations, you end up designing something for everyone,” Wong adds. “Everyone wants more room on the sidewalk. Everyone wants more lighting at night. Having those conversations opens the door to larger ones about identity and representation. Our cities need that.”

More Stories