Rethinking Laboratories

Jacob Werner, Elizabeth Mikula

Fall 2021

On our current trajectory, 49% of carbon emissions will result from new construction between 2020 and 2050, according to research from the Carbon Leadership Forum. The industry’s forward-thinking architects and designers are mobilizing to reduce emissions where they can, but one area is often left out of the conversation. “I’ve seen a lot of research on embodied carbon, but none of it really focused on technical buildings like labs or hospitals,” says Jacob Werner, a Senior Project Architect in our Boston studio.

Without such project-specific data available, Werner and Elizabeth Mikula, a Technical Coordinator, also out of Boston, were trying to figure out a way to talk to clients about how to mitigate the emissions of standard lab materials or find alterative solutions. “Lab material selections are largely dictated by the intensity of the lab,” Mikula explains. “However, not all labs require maximum durability finishes. We see opportunities for flexibility within material selection, including the possibility of introducing natural materials.”

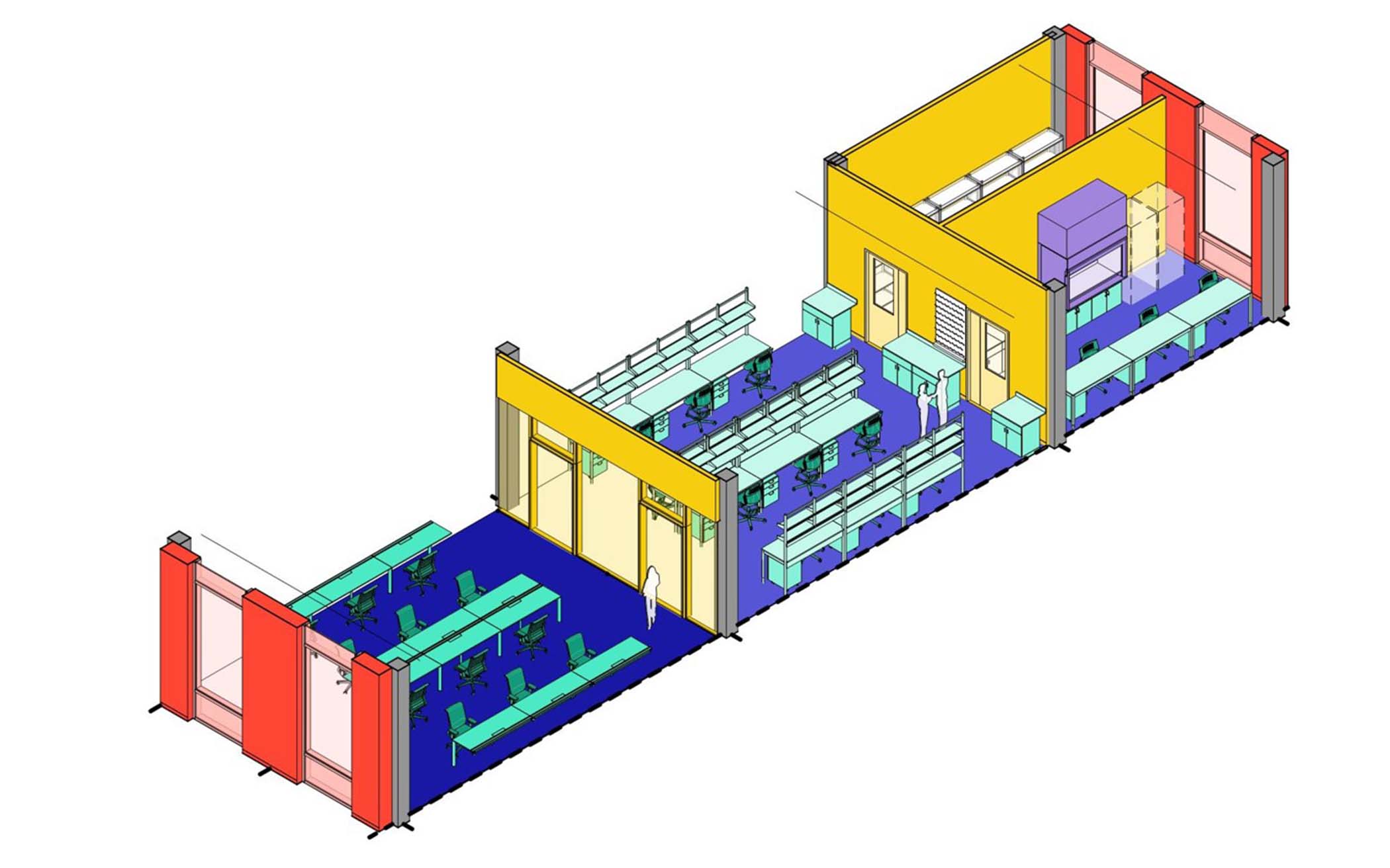

To show how design could reduce emissions and make labs more sustainable overall, Werner and Mikula built the Low Carbon Labs tool, which evaluates a more expansive list of categories than similar calculators and includes products’ Environmental Protection Declarations (EPDs). “We weren’t able to do a full site analysis the way we wanted, so we made our own library in our own tool,” Werner says.

Their method divides labs into three tiers of embodied carbon impact based on materials used in construction or renovation: baseline (labs without any materials to reduce carbon emissions); improved (labs, often renovated, where some materials have been changed and others have remained the same); and reimagined (typically new-builds where materials were chosen deliberately for their reduced carbon impact). In flooring, for instance, epoxy would be a baseline material, rubber an improved material, and linoleum a reimagined material.

Werner describes the Low Carbon Labs tool as a “choose your own adventure” where the user—designers, clients, engineers, etc.—can see where a new or renovated laboratory can cut down on carbon emissions. The tool also calculates total CO2 output and visualizes the data in charts and graphs. As an example, if a team working on a renovation is unable to change the structure of the building or its internal systems, the tool measures the space’s footprint were the team to change less invasive aspects, such as the flooring or casework. Other categories analyzed include lab equipment, doors, and overall structure.

“A client may not be able to choose all the best materials, but you can improve or reimagine certain scenarios in the design,” Werner says. As an added bonus, the tool offers designers and their clients options to make laboratory environments more inviting.

One challenge is the assumed added cost of low-carbon materials in a laboratory project. “But the price of some of these alternative products we’re pitching is comparable to that of standard materials these days,” Mikula says. “We can’t just be relying on outdated idea that everything sustainable is more expensive.”

Currently, the Low Carbon Labs tool is undergoing peer review. Afterward, Mikula and Werner hope to see the tool expanded for use on a variety of projects. Regulations on embodied carbon are probably going to become reality in the next 5 to 10 years, Werner says. The point, however, was not merely to build the tool, but to prove that it’s meaningful, worthwhile, and possible.

“Not only is less carbon better for the world, but it can be beautiful and better for the design, too.”

More Stories