Respecting the Land

fall 2022

In 2021, as the Delta variant of COVID-19 was coursing through Canada, Meadow Musqua’s grandmother was lying ill in a hospital in Saskatchewan. Unable to visit her in person, Musqua and a friend performed healing dances on the lawn outside, but hospital staff initially told them they needed special permission to do so. The land they were dancing on had long been inhabited by their ancestors, and in light of the Canadian government’s ongoing reconciliation efforts, the story made headlines.

The news caught the eyes of Perkins&Will designers Sam Ibrahim and Long Dinh, both based in the Vancouver/Calgary studio. “The efforts to understand that we’re on this land are very strong right now in Canada,” says Ibrahim. “But this story in particular triggered an empathetic response in both of us.”

So they set out to create a process that addresses designing on unceded land (land that indigenous inhabitants never legally signed away to foreign settlers) in hopes of changing the way designers engage with indigenous communities and creating more spaces that make them feel respected and at home. “We asked, ‘How can we celebrate cultural and spiritual practices, like healing dances, in the design of public space?’” says Ibrahim.

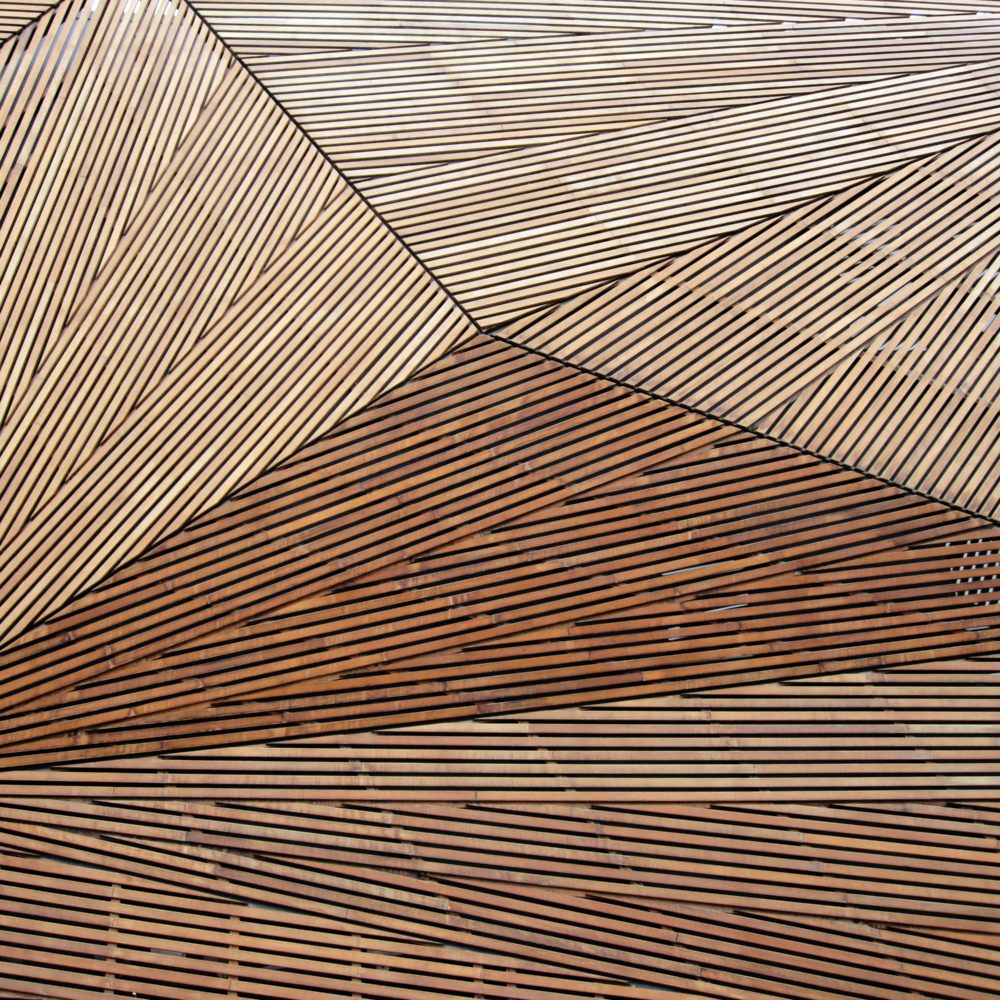

As part of the team responsible for a master planning project that included affordable housing, mental health facilities, and commercial space on the land of the Kwikwetlem First Nation in British Columbia, Sam Ibrahim and Long Dinh (who took this photo) toured the site with representatives from the Nation and BC Housing, the client and current legal owner of the property.

The answer became Designing on Unceded Land, a process Ibrahim and Dinh developed via a research micro-grant that dives into specific nuances in tradition and iconography within indigenous cultures. Their findings explain how those traditions can be honored when designing projects within or near native communities. “Indigenous people are not a monolithic block. Different cultural practices, languages, rituals, and world views all come into play,” Ibrahim says. “It was really important to understand where various cultures are coming from and how they think about the world to design for them.”

The collected ideas, which currently exist in the form of an online whiteboard, act as a gateway for designers to consider which indigenous populations have lived in which regions and the specific cultural nuances that may be important to them. Rather than a strict set of rules, it’s intended to serve as a conversation starter, helping designers engage with local indigenous communities with sensitivity and knowledge before concepting a design that potentially does more harm than good. “Every indigenous nation has a unique way of design, from what typically motivates their art down to subtle differences in weaving patterns or engravings,” explains Dinh. “If you’re on the land of a certain nation, you want to respect that nation and not bring in another artifact or artwork from a different nation just to tick a box.”

The guidelines in Designing on Unceded Land improve the chances that designers, and thus clients, will create a more familiar environment for those whose ancestors previously inhabited the land. “It’s about relationship building. Connections with indigenous communities are built on trust,” Ibrahim says.

Now, the team is thinking about how to make their ideas more accessible. “This approach encourages us and clients to think more holistically about what we can and can’t do on a specific nation’s land,” Dinh says. “Now we just have to make it more deliverable.”

That said, the duo hopes for a time where this process is no longer even necessary. “In the future, if people don’t need to use this because indigenous values are already clearly prevalent in the design, whether through teams being well-versed with the culture or members of the Nation being part of the design team, then we really succeeded,” Ibrahim says. “That’s truly inclusive design.”

More Stories