Tapping Into a Different Kind of Brewery

Celeste Clayton, Megan Recher*

Spring 2019

On their runs around White Rock Lake in Dallas, Texas, the duo would regularly pass the historic Filter Building—a former coal-fired pump house turned industrial wedding venue—and consider the space’s potential. A building of that size and scale could re-imagine different functions, including warehousing a low-impact brewery. “What if you could use geothermal [energy] to heat or cool the beer?” Megan wondered.

Would it be possible to design a brewery specific to the climate in Dallas that would meet the Living Building Challenge?

At the same time, they were talking with a friend-of-a-friend who was interested in producing sustainable local beer in a regenerative space. The mounting curiosity spurred a singular challenge: Would it be possible to design a brewery specific to the climate in Dallas that would meet the Living Building Challenge? “We had talked about this pipe dream,” adds Celeste. “Whenever we ‘grew up,’ this would be something we could do.”

Megan, formerly of our Dallas studio, now living in Utah, was well-versed in sustainable practices. She suggested to Celeste—an architect in the Dallas studio’s Education practice with a bourgeoning interest in sustainability—that they set out to probe the question with an Innovation Incubator grant.

Celeste (left) and Megan were co-workers turned friends who teamed up to explore an area of mutual interest.

LBC is a building standard administered by the International Living Future Institute―an “advocacy tool for projects to move beyond merely being less bad and to become truly generative.”

Read more here.

Tackling Living Design through the lens of one of its threats: the water-guzzling brewery.

The decision to focus on this space typology was strategic: Breweries are notorious for their high system loads, particularly related to water, energy, and waste. And there had not yet been a Petal-certified brewery—that is, one that meets the Living Building Challenge.

Equipped with a clear vision, they got started by visiting local breweries to learn about operations. The grant deliverable was to be a research-based report detailing opportunities and specific methods to decrease water, energy use, and waste by applying regenerative principles.

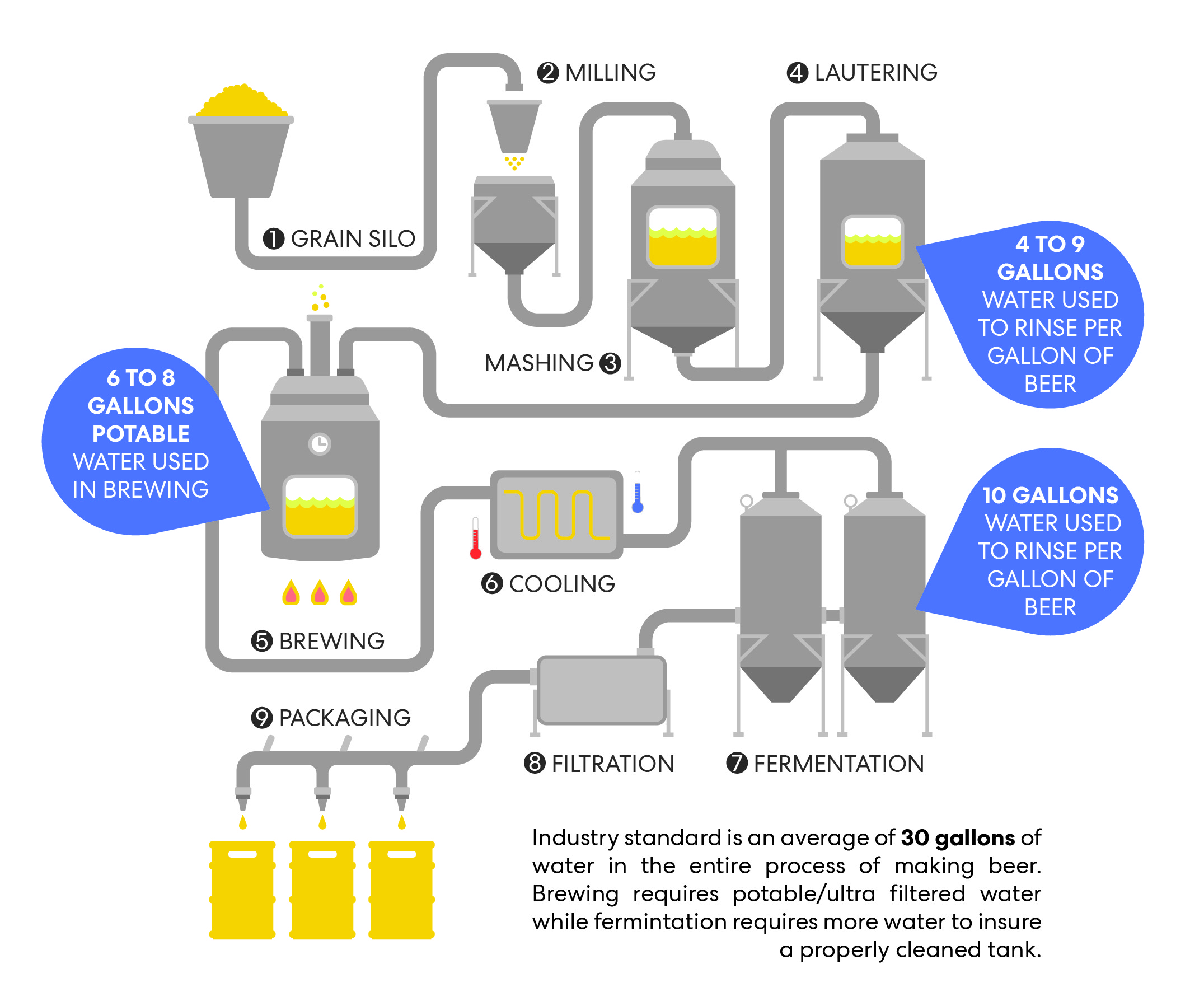

They soon found it takes 7 gallons of water to produce 1 gallon of beer—and that the number can inch toward 10 or more at less efficient breweries. “The amount of potable water that is used to clean and sterilize the tanks is enormous. The cleaning is such a huge guzzler,” says Celeste.

The pair targeted a goal of reducing potable water usage by 65% through more efficient systems, collect the rest of the potable water through rain and humidity, and implement a closed-loop system for all water processing. Beyond water, they also detailed specific recommendations for reducing the energy needed for brewing and the overall waste generated.

“What if water goes away? What’s the trickle down to community? And what can we do now to make sure we still have water?”

― CELESTE

It all flows from water—and other lessons learned from the Incubator.

Celeste and Megan both enjoy beer and have an appreciation for the brewery’s role in community building. But the core of this project was about preserving fundamental resources. “Even if it’s not looking at beer specifically, what if water goes away?” Celeste explains. “What is the trickle-down to goods and services? What’s the trickle-down to community? And what can we do now to make sure we still have water?”

“The [Innovation Incubator] program is not specific to architecture, which was kind of a breath of fresh air. It is really cool to see the diversity of thought.”

― CELESTE

Their conclusions? It was indeed possible to create a net-positive energy brewery. Working with a friend on a passion project is a whole lot of fun. And there is value in not just educating clients and partners (they have started sharing their findings with local breweries)—but also your own colleagues. Celeste and Megan structured their report to be widely applicable across the firm as an educational tool with helpful, research-driven rules of thumb that can be applied to other building types.

The way they explain it, Innovation Incubator allowed them to enhance their knowledge of Living Design principles and to contribute to a collection of ideas that improve how we design for people. “[The program] is not specific to architecture, which was kind of a breath of fresh air,” says Celeste. “It is really cool to see the diversity of thought.”

Adds Megan: “A lot of companies say they support your own research. But Perkins&Will actually does it.”*former Perkins&Will employee

More Stories