Designing for Everyone

fall 2021

The most successful places are those designed with careful attention to the different ways people experience their environments. How might a patient with auditory sensitivities navigate a hospital environment that relies on PA systems? How does a warehouse worker with visual impairment find their way through a sea of nondescript aisles? Does the typical office meet the ergonomic needs of an employee with a brain injury that alters their physical abilities?

These examples merely scratch the surface: Roughly 15-20% of the population experiences some form of neurodivergence. Now, a new resource prompts architects and designers to think even more broadly about whom they’re designing for, and empowers them to create workplaces that support people with diverse physical and mental abilities: The Neurodiversity Toolkit.

Created in 2021 via a research micro-grant awarded to Perkins&Will designer Jesce Walz and a former colleague, Georgia Metz, the incubator and resulting toolkit helps designers understand neurodiversity in the workplace through principles of biodiversity. How? By reimagining our built environments as ecological ones, where many different species can thrive at once.

“We can create some really interesting, artful spaces with the intent of supporting a more diverse set of people when we learn from ecology,” Jesce says. “Just as the natural world supports a host of species with different evolutionary attributes, so could a space that takes into account the array of neurological differences within human beings.”

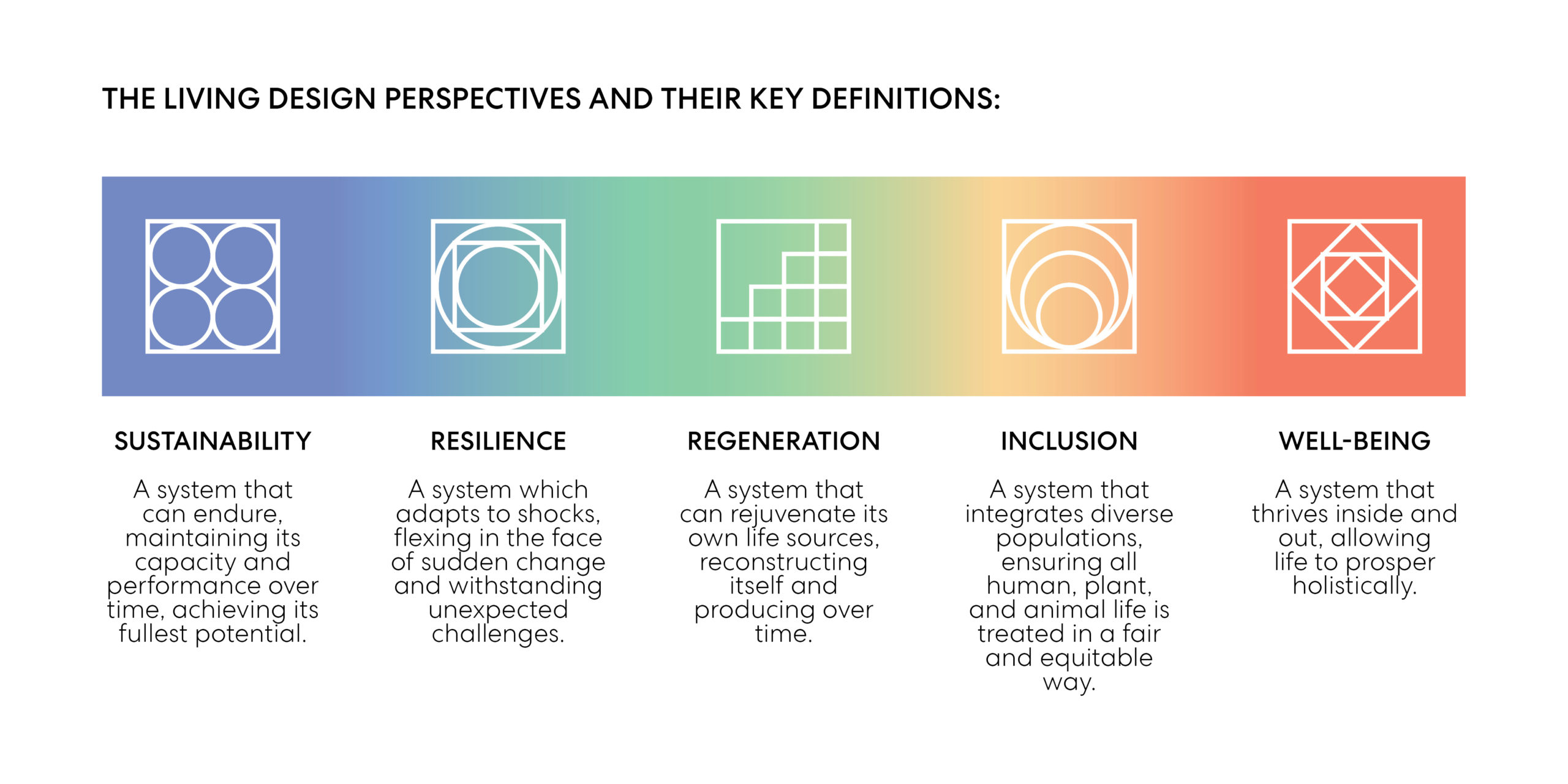

To build the toolkit, the team evaluated varying neurological needs and consolidated them into six experience categories: audible, visual, environmental, physical, social, and cognitive. Then, they examined seven areas in which these differences can be addressed in the design process: site, circulation, interior environments, workspaces, collaborative spaces, amenities, and equipment and furnishings. Using the toolkit, a designer might see how minimal, simple floor patterns can aid people with visual impairments. Or how zones separated by easily distinguishable walls, dividers, or color themes help people who may need auditory, environmental, or social support all at once.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What might we learn from a space that supports a wide range of life?’” Jesce explains. “That question helped us think about, for example, how we might design a space with someone who needs a lot of stimuli and someone who is hypersensitive to too much stimulus at the same time.”

Their research included several lessons from ecology, such as how the transition area between two distinct habitats (called an ecotone) often supports a wider variety of species than the individual habitats themselves. In terms of design, that translates to entrances, corridors, and connective spaces that accommodate the diverse needs of different people. For example, designers of emergency evacuation areas and pathways need to be especially aware of how a variety of people respond to strobe light frequency, color, alarm decibels, and crowd management—and then design compassionate, humane solutions that address those sensitivities.

Office environments designed for neurodiversity also tend to attract more diverse teams, which has direct economic benefits for employers. The team also discovered in their research that more diverse workplaces are more profitable than their competitors.

“A significant portion of the population identifies as neurodiverse. Designing without them in mind is a missed opportunity for employers, and not just because it risks low employee retention. Designing for neurodiversity is simply a better, more helpful way to design space for everyone,” Jesce says. “Who wouldn’t want that?”

More Stories