On the Cusp of Something Big: Designing for the Rise of Esports

Scott Schroeder, Jenna Cruff*, with support from Lee Sterrett and Jamie Benallo

Spring 2018, Fall 2018

In fact, competitive gaming is a $1 billion business, with projected viewership of 84 million by 2021—more than every other professional sports league except the NFL. It has cultivated an impressive, rapidly expanding ecosystem, encompassing giant arenas, professional leagues, academic degrees and scholarships, and loyal fandom.

Scott, the director of visualization in our Denver studio, has been tracking this rise closely. An avid gamer himself, he and former colleague Jenna wanted to get it on the radar of his colleagues, many of whom work in the firm’s Sports, Recreation and Entertainment practice. An Innovation Incubator grant offered the chance to assess the esports landscape and bring more visibility to the sport and the space typologies associated with it.

“It was the perfect opportunity to convince people that esports is a legitimate thing, and we really need to be paying attention to it,” he says, and where other sports have been waylaid by the pandemic, esports seasons can continue. “It’s already exploding, and it’s only going to go up more—especially given the pandemic.”

“It was the perfect opportunity to convince people that esports is a legitimate thing, and we really need to be paying attention to it.”

― SCOTT

Scott, his dog, and a quintessential 1980s laser background.

Colleagues, including Lee Sterrett and Jamie Benallo—who both provided research support and advocacy—recognized the potential from a business development standpoint. The team began by investigating the history of competitive video gaming and its current issues—including equity. Esports is still a boys’ club. Only a small slice of professional players are female, and the earning gap between women and men is a staggering 718%. Additionally, gaming has historically been plagued by an exclusionary and misogynistic culture, fueled by the anonymity of playing online.

“I was shocked to learn that if a person has one negative experience gaming online, there’s a 300% chance they will not return to that game again,” he says. “So the idea of a the toxic gaming environment has to be solved—and that’s partially why the push into middle schools is so important. If you get kids playing with other people in the same room, you learn teamwork and empathy.” Scott also points out that the growing esports ecology in schools is not just about playing the games, but also all the affiliated activities like video game writing and broadcasting. Fostering this framework is a key path to making the sport more inclusive.

If this Innovation Incubator—Esports Rising—was the “why” behind esports, then a second grant six months later was the “how.” Here, Scott and Jenna made the case for a specific area of focus: K-12 schools and higher education. The goal with the second report was crafting a set of recommendations for implementing a program.

The team toured esports facilities from small venues to Esports Stadium Arlington in Texas, the largest dedicated esports facility in North America. “We were able to go behind the scenes and get great insight,” says Scott.

From these conversations, they identified a few findings: They would need longer desks to accommodate different postures (as posture is critical to both reducing injury and improving performance); and they would need to invest in designing around power (in floors and walls), as power is the most integral element of the sport. “We were approaching this from a make it cool first, functional second standpoint,” says Scott. “And this flipped our assumptions.”

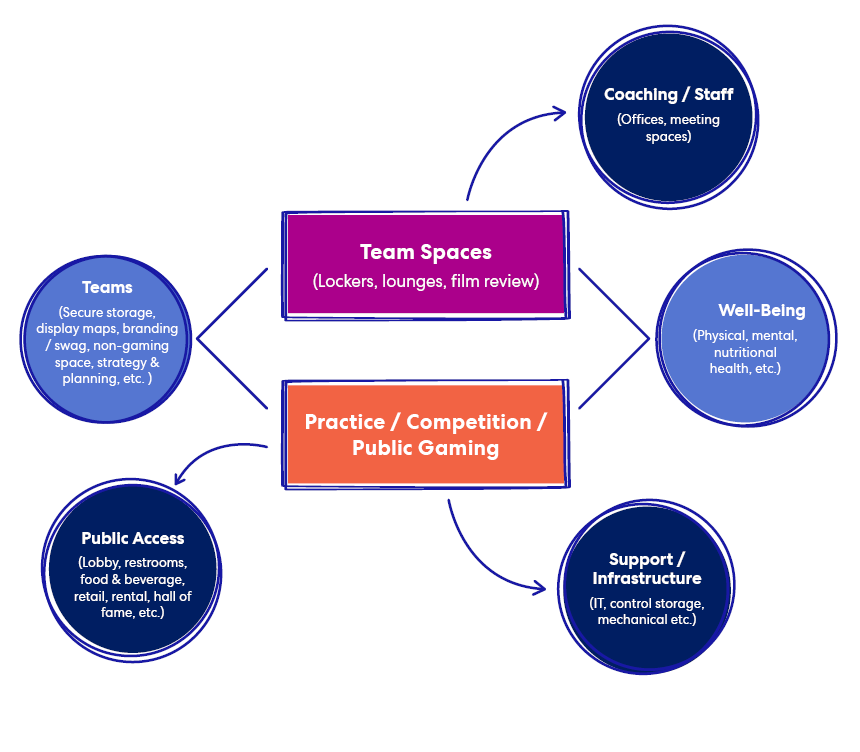

The team proposed best practices for the design of esports facilities at various scales.

Their research and conversation guided their creation of a scalable program, series of floor plans, and the necessary components and considerations for different esports spaces—what Scott calls “building blocks.”

“Since our two incubator submissions, we have found ongoing value for our efforts,” says Lee. “ We have shared the data with our other studios and clients; we have used it for interviews and as an expertise differentiator,” he adds, pointing out that their new expertise has helped them win projects, including the Minnesota Timberwolves Training Facility.

Now, Scott is hoping to plant the seed in the education practice and begin to leverage the knowledge he’s gained. Might there be a part three to the report? If so, one area of potential research, Scott says, would be green technology and energy with the goal of reducing the power requirements of esports spaces.

What components do we consider in the design of esports facilities?

“I now feel empowered to have informed conversations with our professional, collegiate, and recreational clients who might be considering adding esports programs.”

― JAMIE

Scott shares that the Innovation Incubator program was a powerful vehicle for socializing his idea internally and building a case for its value. “A lot of studios may want to look at new ways of doing things, but maybe don’t have the extra time or resources,” he says.

“I think this is an amazing program to force these ideas to bubble to the top,” says Scott, noting in particular the role that Jamie and Lee played as advocates. “Had we tried to push it up the normal chain of command, it would have happened—but it wouldn’t have progressed as quickly.”

*former Perkins&Will employee

More Stories