A Scientist and a Designer Walk Into a Room: Creating Conversation to Improve Health Outcomes

Meredith Kinney

Fall 2016

That is to say, most will know about—or will have even been directly impacted by—the scientific breakthrough that opened the door to new methods of diagnosing, treating, and curing diseases.

Learn more here.

But ask them about the Human Exposome Project? Well, expect more blank stares. Meredith, a senior Branded Environments designer in our Atlanta studio, wondered why this was the case. After all, the exposome can account for 80-85% percent of disease risk, whereas only 15-20% can be attributed to the genome.* (The exposome is the “nurture” to the genome’s “nature.”)

Meredith’s interest in the topic was sparked, fittingly, by frequent exposure to it. Her father-in-law, Dean Jones, Ph.D., is a Professor of Medicine and Director of the Clinical Biomarkers Laboratory at Emory University. Living nearby, Meredith would frequently hear him talk about his research with exposure science—and became fascinated with how lifestyle affects the body. She saw potential for two parallel paths to intersect for the mutual benefit of scientists and designers.

“His work connects to the work we do [as designers] in terms of material health,” she explains. “The things that the scientific community and design profession are exploring can inform each other in more meaningful ways.”

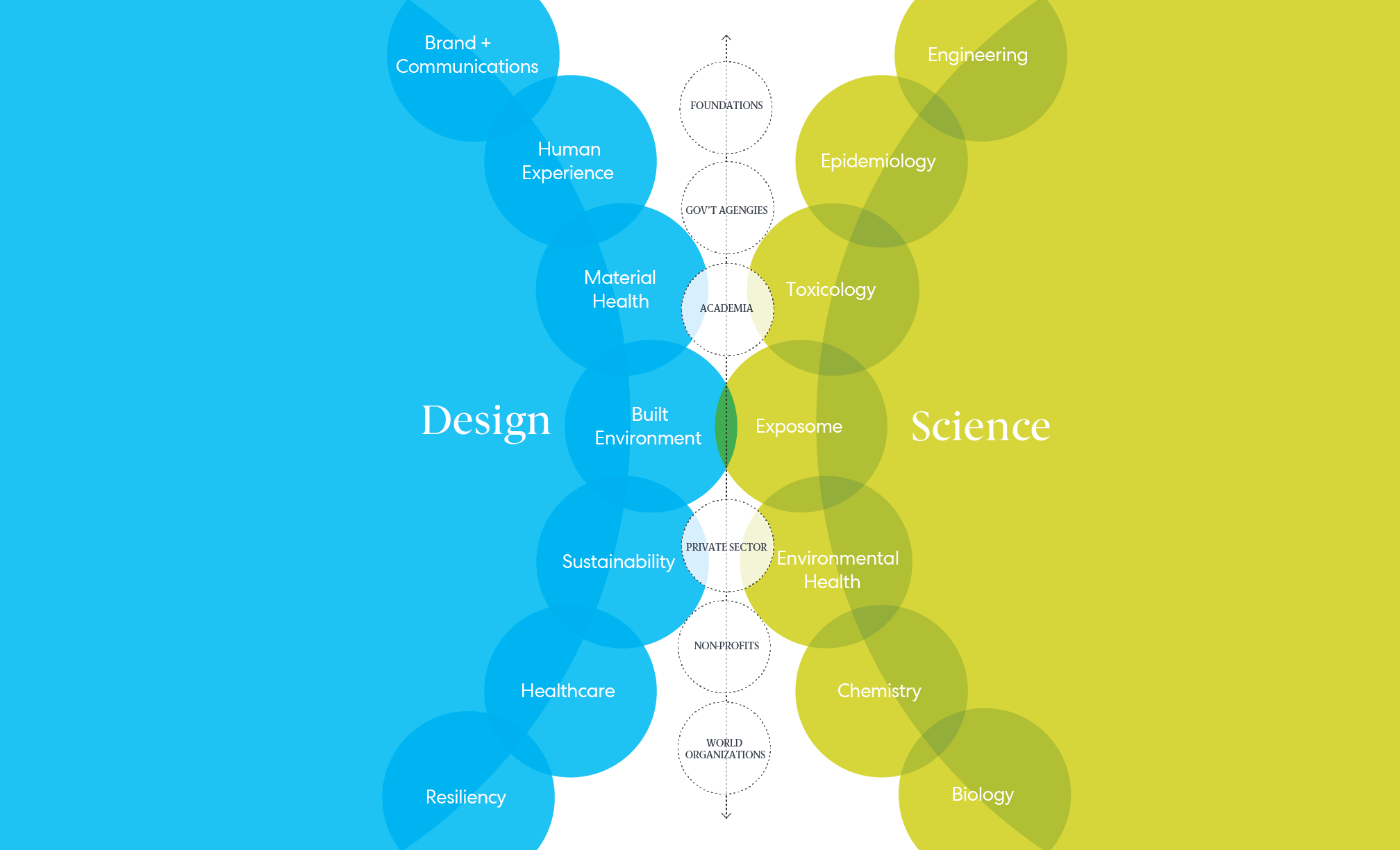

The fields of science and design can intersect, coalesce, and influence one another to solve today’s pressing problems.

“Does the exposome need to be rebranded?” Meredith recalls pondering as she began her project. She points to the accessibility and tangibility of the human genome “brand” with the advent of popular direct-to-consumer DNA tests like 23andme. How might she wield her brand strategist skills to raise awareness about the exposome?

And so a lingering question became the basis of an Innovation Incubator project, a symposium convening people with different backgrounds and expertise to discuss a shared concern: the impact of those environmental exposures over the course of a life, from diet and lifestyle to the building materials where we live, work, and play.

“There are so many things we can learn from science that we can practice more robustly in design.”

― MEREDITH

Meredith’s role in the Branded Environments group meant working with clients to craft messages and experiences that illuminate their mission, vision, and values. Through this lens, her symposium was akin to a visioning session that she might execute for clients—getting the right voices at the table and facilitating a conversation to elicit key takeaways.

Attendees at the one-day session included scientists and designers, as well as individuals from academia, government agencies, nonprofits, and the private sector. Elaine Cohen Hubal of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Erica Hartman, Ph.D. from Northwestern University, Perkins&Will thought leaders, including Robin Guenther and Paula McEvoy, and myriad specialists all rubbed elbows.

Meredith assembled a group of experts from different fields to discuss a shared goal: reducing the negative impacts of our exposures on our health.

Perkins&Will’s compilation of the most ubiquitous and problematic substances that people encounter every day in the built environment—housed on our Transparency site.

The agenda included roundtable discussion to illuminate questions, challenges, and discoveries. The group also took the opportunity to parse the Precautionary List. Finally, they formulated some action items. Among their takeaways: There was potential to create a consumer perception shift if they could more clearly link biological risks to certain materials—but to do so, concluded Meredith in the report, “The identity and communication of the exposome must be clear, ownable, and powerful.”

Among Meredith’s personal takeaways: “There are so many things we can learn from science that we can practice more robustly in design,” she says. “Leveraging the science can make the case for our approach to sustainability, as designers, stronger.

“I’m not a scientist, nor a material health expert,” she says. “I was facilitating the conversation between people who had missions that could align.” No doubt this dot-connecting role is critical when it comes to conversations about human health—a position of particular importance in our current pandemic.

Meredith and her family

The project offered an opportunity to draw upon some of the best and brightest minds. “You can’t just go in a hole and innovate,” she says. “You need a network of people who are going to support you.”

And then there’s the autonomy piece. “Innovation Incubator is a good way of picking your client, in a sense. You’re the owner of how that project works,” she says. “It feeds your entrepreneurial spirit in a good way.”

*Jones et al 2012 Annu Rev Nutr 32:183-202; Miller and Jones 2014 Toxicol Sci 137:1-2

More Stories