A New Formula for Neighborhood Livability

Annie Ryan, Ivy Cao

Fall 2019

“But what’s missing is an understanding of the social nuances—of what is enabled when we build these good neighborhoods and what might actually be prevented.”

Ivy, an urban designer with a Master of Science in data analytics, was also bothered by this shortfall. That they were both based in our San Francisco studio—in a city with a well-documented housing affordability crisis—put access and equity into even sharper focus. The two women wondered if there was a better way to expand the catalog of metrics used to define “good.”

Ivy pushed to formalize the inquiry with an Innovation Incubator grant. “We cannot ignore the data around us anymore,” she says, about harnessing it for the urban design practice at large.

― IVY

Ivy

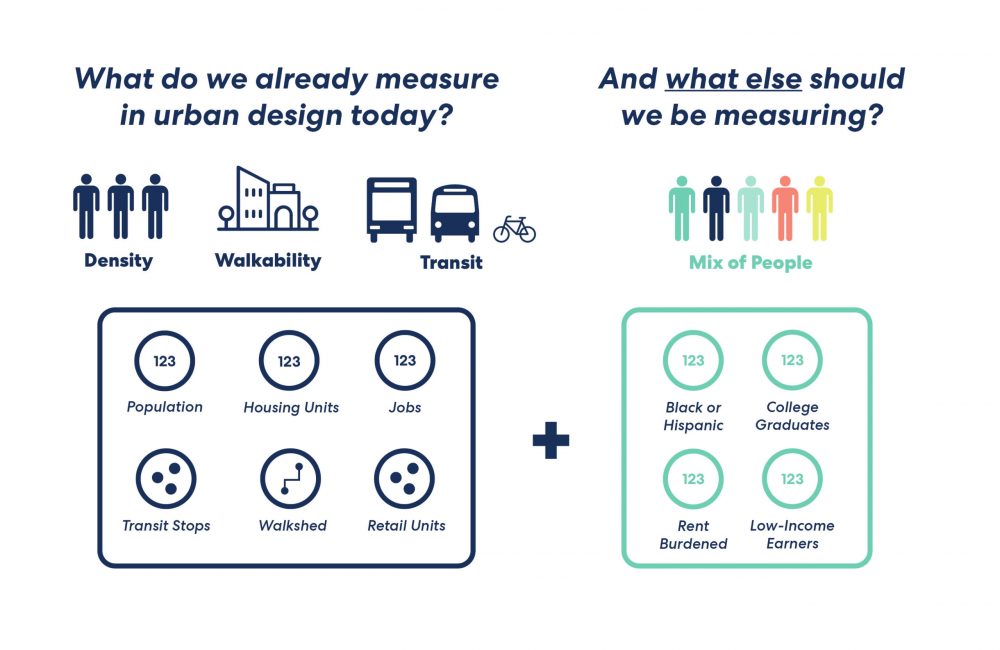

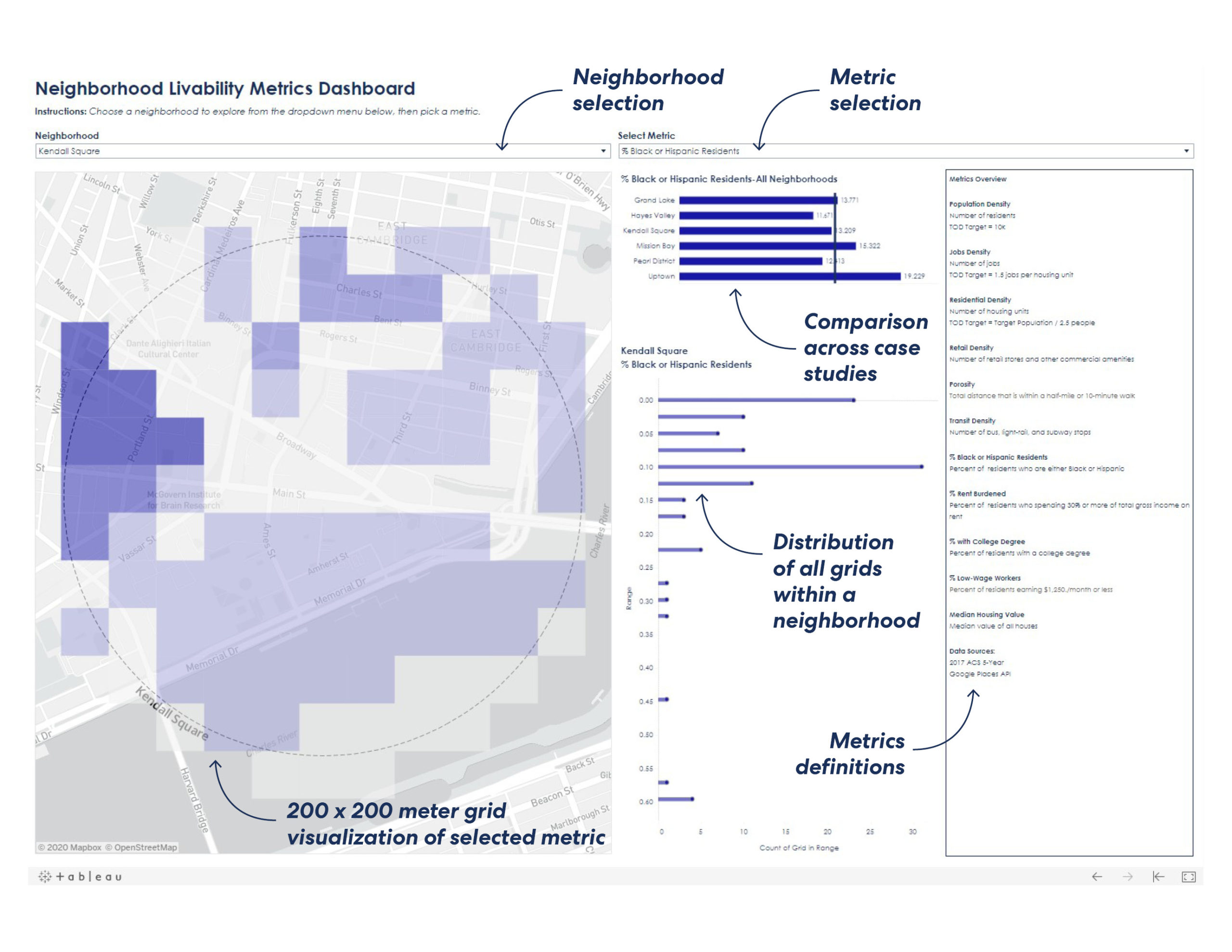

And from there, a bold vision emerged: Equip urban designers and planners with a set of “socialized” metrics—including percent of rent-burdened residents and median home value—to complement the typical metrics used in transit-oriented development (TOD) projects. An overarching goal was to make it all “bite-sized” and accessible—to ultimately facilitate conversations with clients and stakeholders about how urban design policies impact equity.

By looking at what was traditionally measured in urban design, Annie and Ivy were able to identify critical gaps.

The team used Tableau to track and display their new metrics of livability.

While Annie and Ivy started their project in a time of heightened awareness around equity, they couldn’t have anticipated how urgent their work would become. By the time they presented the project to the Innovation Incubator Committee in June 2020, the world had changed. The killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor had created a groundswell of dialogue and activism around race. In the discourse about overt racism and police brutality, the more surreptitious parts—like the history of red-lining—emerged. “There’s been a real reckoning,” says Annie. “Because all of the unrest, we see in our cities how it connects to the racist practices of our predecessors.”

― ANNIE

Annie

The project has attracted the attention of various groups in the firm, including our Diversity Council and various Research Labs. Eunice Wong, an urban designer and planner in our Toronto studio, connected with Annie and Ivy as part of the Living Urban Districts research project. She touts the Incubator project’s robust methodology and capacity for changing how we understand neighborhoods. “It’s challenging us to deepen our ‘so what’ in order to tell accurate and meaningful stories.”

A joint collaboration between three of our Research Labs, Mobility, Human Experience (Hx), and Resilience, this research project will address resilience planning at the district level through the lens of four case study cities.

As Annie and Ivy tell it, Innovation Incubator put some stature behind their exploration. It allowed them to step away from work tasks, and, perhaps paradoxically, this step away will make their future projects better. “We are seeing a desire for this type of thinking to be embedded in our projects—but it may not have happened on its own,” says Annie.

Now, they want to continue to collect data. “The more points we gather, the more intelligent the database will become,” says Ivy. They also will continue their advocacy for frank dialogue about neighborhood equity. “We already believe in the power of data to change people’s perceptions about the places,” says Annie. “Now, we just want to open the aperture a bit so that we can actually deliver something that we can stand by when it comes to equity and inclusion.”

More Stories