Rethinking How California Can Live with Fire: A Guide for Intentional Burning and How to Design Going Forward

ADDISON ESTRADA, HELEN SCHNEIDER, AND MARAYA MORGAN

FALL 2020

Long before humans, nearly 4.5 million acres of California’s wildlands burned every year, according to a research report by the University of California Berkeley. But the nature of this phenomenon—amplified by climate change—has transformed in recent years. Residents’ homes, communities, and quality of life are increasingly becoming threatened by catastrophic blazes of unmatched proportions. This new reality requires adaptation. It also requires knowledge of how to respond to, and with, fire in a strategic way.

A team of researchers in our San Francisco studio has made it their mission to help. Their report—”Living with Wildfire: Exploring A Resilient Future for Fire Prone Areas” by Addison Estrada, Maraya Morgan, and Helen Schneider—condenses research findings and recommendations from a wide range of experts. So that nonexperts can integrate wildfire resiliency into their projects, it also explores best practices in land stewardship, neighborhood planning, and building in the face of heightened fire risk. They put forth multiple approaches, such as legacy methods upheld by Indigenous people and new techniques developed by Western fire consultants. Below, we’ve summarized the report’s recommendations for design professionals, developers, and homeowners.

In 2020, five of the fires that burned through California ranked among the largest in the state’s recorded history.

Firefighters preventing a Santa Ana Winds-driven fire from jumping Highway 101 in Ventura.

Treat Fire as Friend, Not Foe

For the past 60 years, California has experienced an abnormal trend: wildfires with no means of containment—known as megafires—as well as longer fire seasons. This indicates a lack of equilibrium in the ecosystem. Human efforts to suppress fires, rather than allowing dense, unhealthy forests to undergo natural management through fire, is a factor that is partially to blame. Controlled burning is a mechanical simulation of natural wildfire that strategically uses low intensity fire to reduce the build up of dead or dying combustibles, encourage new growth and promote more wildfire resilient landscapes. This type of intervention can mitigate the spread of these wildfires and cause less destruction.

In fact, Indigenous People used this method to cultivate land for nearly 11,000 years; it is sometimes referred as “cultural burning” on account of its ceremonious nature. But when Spanish settlers colonized the land, they were intent on capitalizing off logging, agriculture, and mining, and viewed controlled burning as a threat to commodified resources. Their solution was to ban Indigenous peoples’ practices. The prejudice against cultural burning was later compounded by the Big Blowup of 1910, a devastating wildfire that torched 3 million acres of private and federal land in Montana and Idaho, taking the lives of 85 victims—78 of whom were firefighters.

Subsequently, fire suppression policies convinced society that we needed to defeat fire rather than work with it.

Forested landscape after a megafire caused by an illegal campfire in Garrapata State Park.

Unfortunately, these policies have created negative long-term effects in the state of California. By prohibiting controlled burning and instead allowing the dense growth of trees and underbrush, which contributes to what researchers call “fuel load,” we are actually more prone to larger fires. In 2020, for instance, five of the fires that burned through California ranked among the largest in the state’s recorded history.

Today, as severe wildfires ravage communities across the Western U.S., we’re at an inflection point: We must change the way we think about fire. Indeed, we must harness the power of fire so that it works for us, not against us.

“Fire is not the enemy. Fire is a natural process that has happened for millennia. We need to prevent the cycle of catastrophic megafires,” says the report’s co-author Helen Schneider.

“We have the opportunity to… start planting seeds about [controlled burning] practices…”

― HELEN

The paved road acts as a fuel break for a spreading fire in Bonny Doon Spring.

Fortunately, firefighters and forest management personnel are beginning to make the shift, and the practice of controlled burning is undergoing a resurgence of sorts. In Oregon, for example, the spread of the July 2021 Bootleg Fire, one of the largest burning megafires in the country, was quelled with controlled burnings. At least one reputable news source reported that the fire had slowed and inflicted much less damage when the flames reached the Black Hills Ecosystem Restoration Project, an area where the Klamath Tribes and U.S. Forest Service had thinned young trees and applied prescribed burning.

Clearly, such management techniques can make it less likely that a small fire grows to the scale of a megafire and provide confidence for other communities looking to adopt best practices.

“We have the opportunity to… start planting seeds about [controlled burning] practices because we have clients who are land managers in and adjacent to wildland areas” Schneider says. “This approach to fuel management has the added benefit of supporting and sustaining diverse ecosystems.”

“Fire is not the enemy. Fire is a natural process that has happened for millennia. We need to prevent the cycle of catastrophic megafires.”

― HELEN

A fire moving up a hill during the Camp Fire in Paradise.

Shift Developmental Practices

The location of new residential developments is another factor in the level of destruction fires are causing. Between 1985 and 2013, 50% of structures destroyed by wildfire in California were suburban developments situated next to wildland. Referred to as Interface, or Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI), these developments can act as fuel when the fires move from the natural vegetation to buildings, which greatly increases the potential for fires—especially in any already dense, dry climates. Residences built next to the wilderness also experience the most damage. The Town of Paradise, which was leveled by the Camp Fire in 2018, is a telling example, claiming close to 19,000 structures and, tragically, 86 lives.

To mitigate risk, the report’s authors suggest that communities integrate more space between wildland areas and residences. Roads can act as potential fire breaks if you keep the edges clear of fuel build up. And if a property has a road leading to it, keep it clear of overwhelming vegetation so emergency personnel can access it. While this won’t guarantee total safety from fires, it can help prevent the fire from spreading from structure to structure.

“There needs to be an acknowledgment that if you’re building in an area that faces fire seasonally, you run that risk of possibly losing your home. It’s necessary for everyone to understand the risk that they’re accepting,” says co-author Addison Estrada.

It’s a topic that hits close to home for him: Estrada’s father has been in California’s fire service for 20 years and is now the Deputy Chief of Fire Prevention at the Santa Clara County Fire Department. And his cousin is a “hot shot”—a specialty wildland firefighter who responds to the riskiest parts of large fires across the country.

“I personally wanted to explore how development trends affect fires and how we, as architects and designers, can better serve the firefighters on the ground protecting people.”

Vehicles melted on the side of the road that were in the Camp Fire’s path of destruction.

“… If you’re building in an area that faces fire seasonally, you run that risk of possibly losing your home.

― ADDISON

Build Resilience From the Inside Out

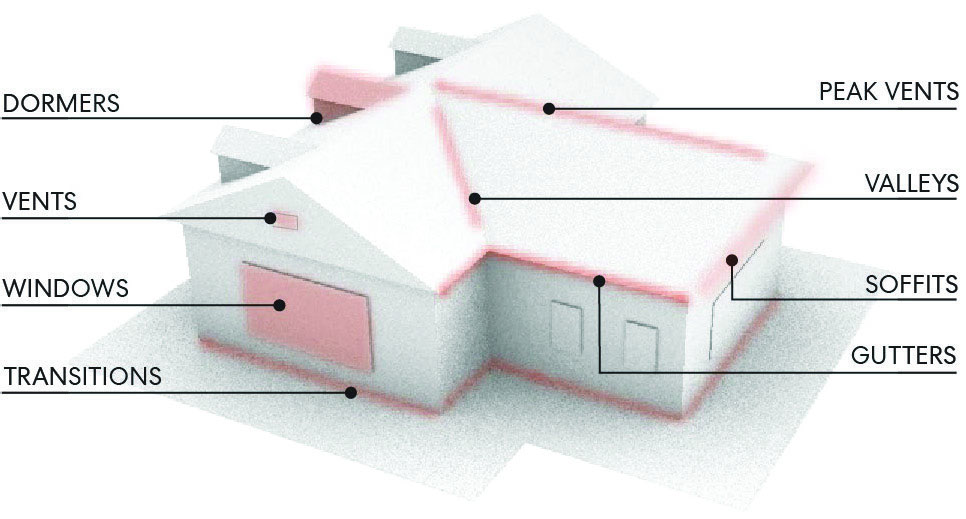

For residents living in areas that are prone to wildfires and looking to fortify their residence, they can take on “home hardening,” a process of safeguarding the most vulnerable areas of a residence from heat, flames, and embers. Methods include installing noncombustible roof, creating a five-foot-zone around the home devoid of fire catching materials (i.e. mulch, furniture, and wood decks), and installing weather stripping around doors to prevent burning debris from getting inside. Home hardening will improve the chances that a home or structure will resist ignition in the event of a wildfire, but if nothing else, it can also help reduce the spread of airborne toxins during burning.

“… Our response should not be fear. It should be motivation to get creative and find solutions.”

― ADDISON

The above illustration highlights the Pointes of Ignition for residences.

Urgency’s Humbling Effects

If the landmark report recently published by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is any indication, the time to implement these aforementioned practices is now.

Climate change’s effects are worsening fire seasons by creating higher wind conditions and drier environments with warmer winters, thus depleting regular snow and rainfall. Simply put, there will be more fire because the climate is warmer.

Smoke and particulate matter blocked out the sun and turned the sky a deep orange from fires in the Pacific Northwest in September 2020.

Ultimately, the architecture and design industry, including real estate developers, city planners, and individual homeowners, has a responsibility to do more, and now, to protect and preserve California’s natural and built ecosystems. By gaining a deeper understanding of the role of wildfire, along with the variables that affect fire’s spread, we can create more resilient design solutions everyone will benefit from.

“There’s an inherent danger to fire, of course. But our response should not be fear. It should be motivation to get creative and find solutions. The more we understand the risk, the more we can make sounder decisions that protect us and our environment,” says Estrada.

More Stories