A Vision in Green

Micah Lipscomb

Spring 2012

A landscape architect based in our Atlanta studio, Micah’s role allows him to touch a wide range of projects—from parks to universities to hospitals—and he brings a strong appreciation for nature (and resourcefulness in working with it) to each one.

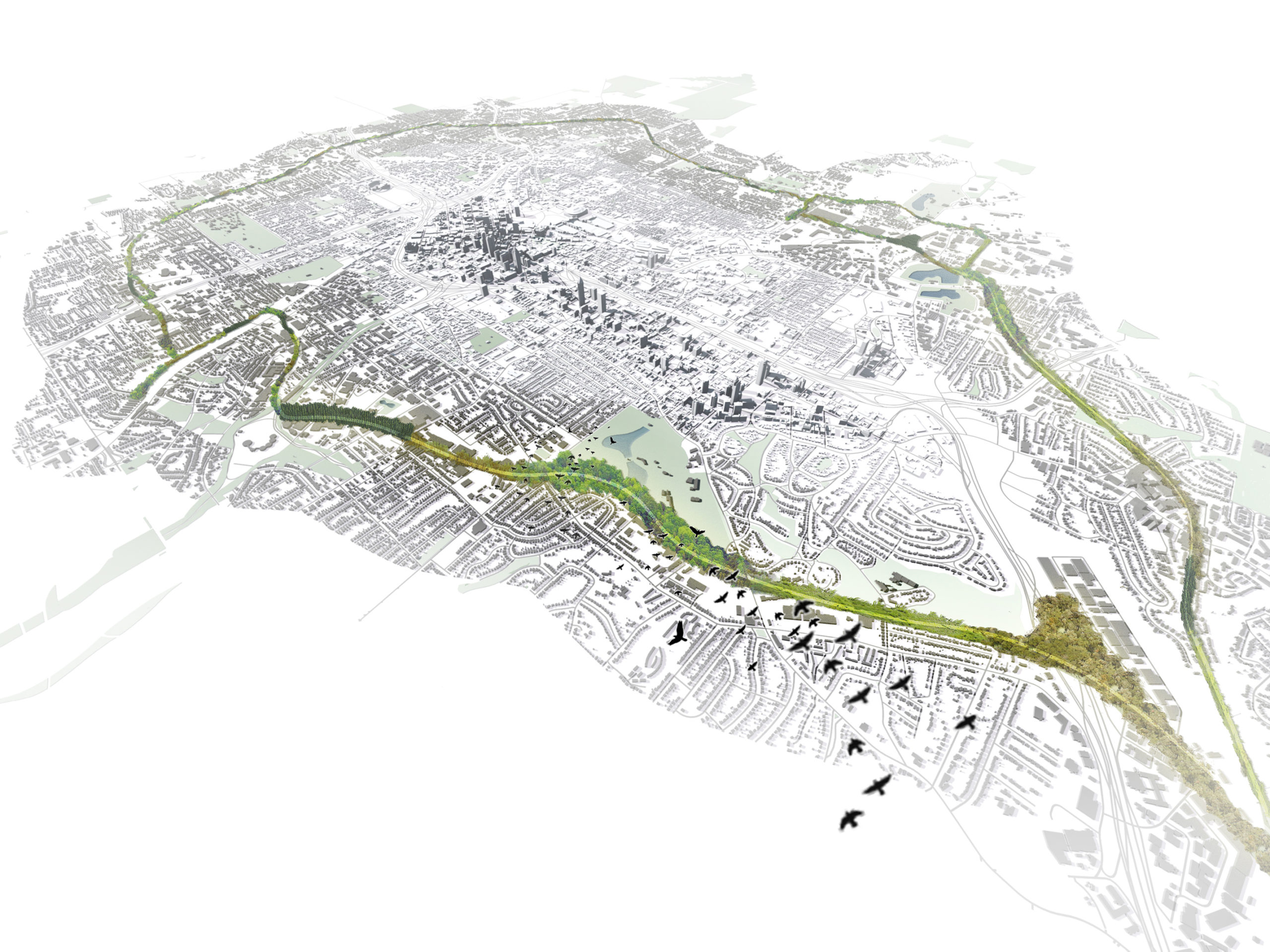

The Atlanta BeltLine is a large-scale urban redevelopment program that transformed old, abandoned railroad tracks into a 22-mile multi-modal corridor featuring public transit, a linear greenway, and multi-use trails, equal parts journey and destination.

Read more here.

One such project—the Atlanta BeltLine—provided a launching point for an Innovation Incubator. Micah was inspired to conduct an independent study on vegetated (“green”) tracks, or those with grass or sedum planted between them. Though implementing this approach was not part of the project scope, Micah wondered if he could help the BeltLine execute its vision of becoming a linear gateway by packaging up some best practices and recommendations for the client.

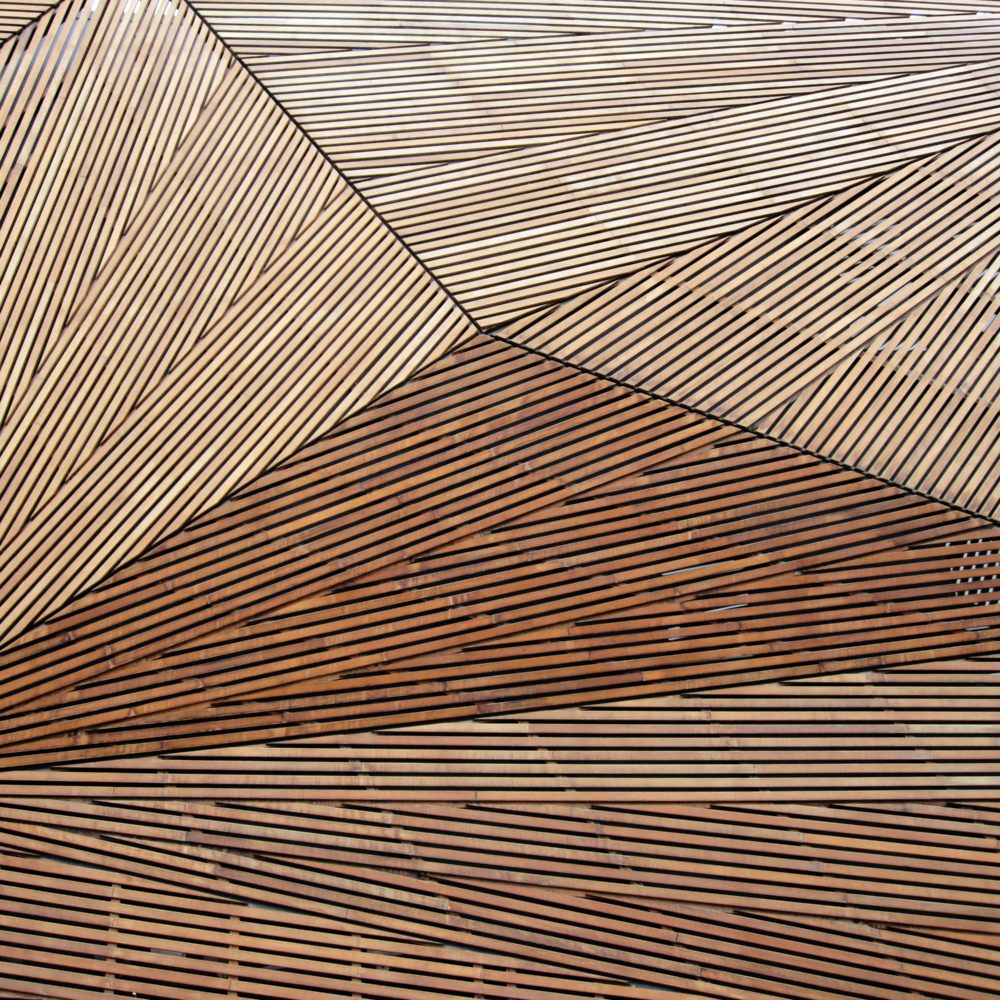

Use the slider to compare renderings of the Atlanta BeltLine’s Ponce Overlook―with and without green tracks.

Micah’s research involved evaluating examples of green tracks in various European cities—Europe being more likely to invest in this approach—as well as Fort Collins, Colorado. “And then I had to learn the basics of train design,” he deadpans. “It was a fun kind of deep dive.”

The benefits of green tracks over standard ballasted tracks were clear: stormwater absorption, noise reduction, dust mitigation, reduction in urban heat island effect, and improved aesthetics. But the question of how to implement the approach in Atlanta and “sell” the return on investment remained.

Micah put the opportunity in context: The Atlanta BeltLine represented about 22 miles of rail. Multiplying that by 30 feet (of typical width) equaled about 80 acres of potential impervious area—or the equivalent of 4 miles of Atlanta’s 14-lane interstate highway.

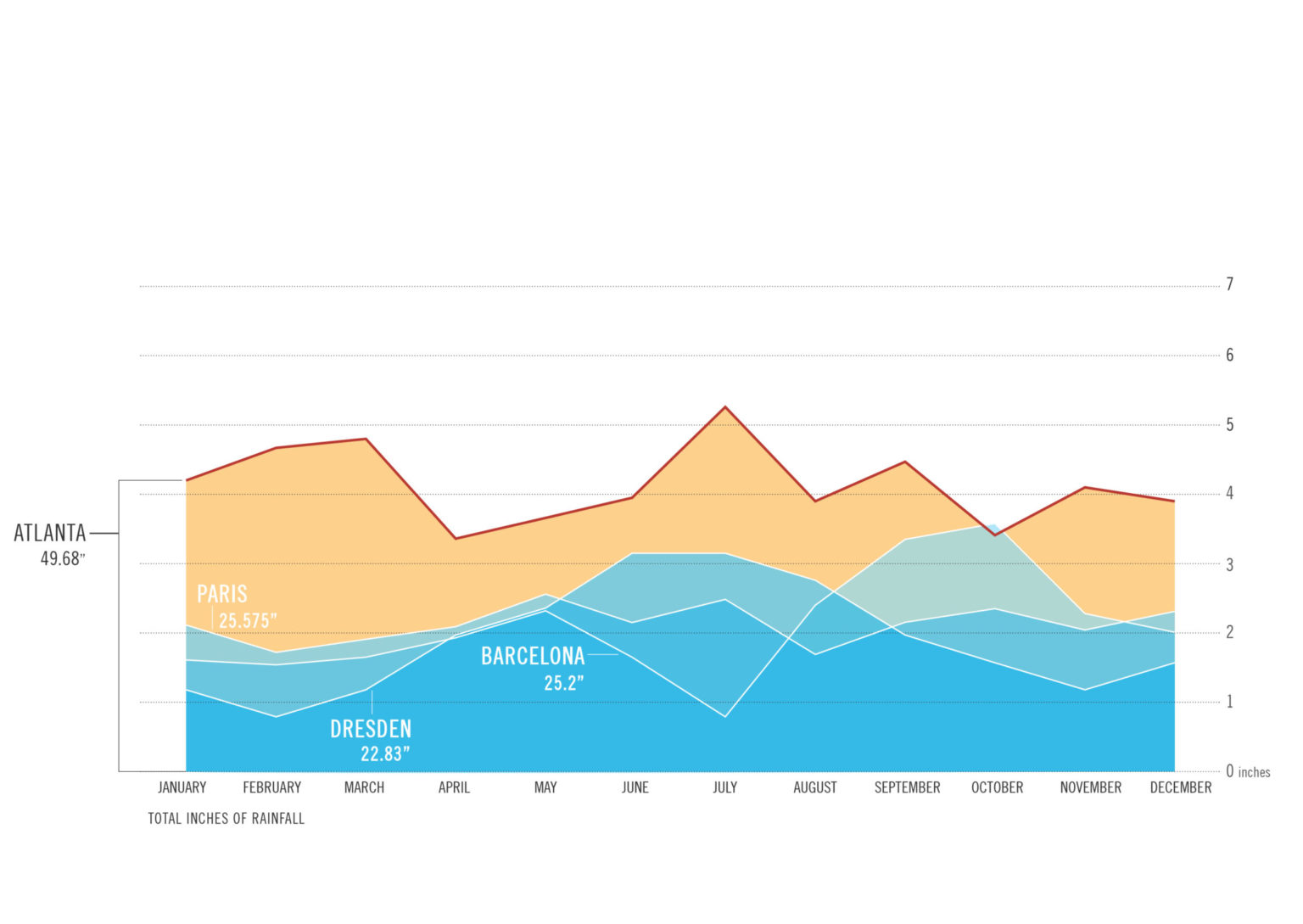

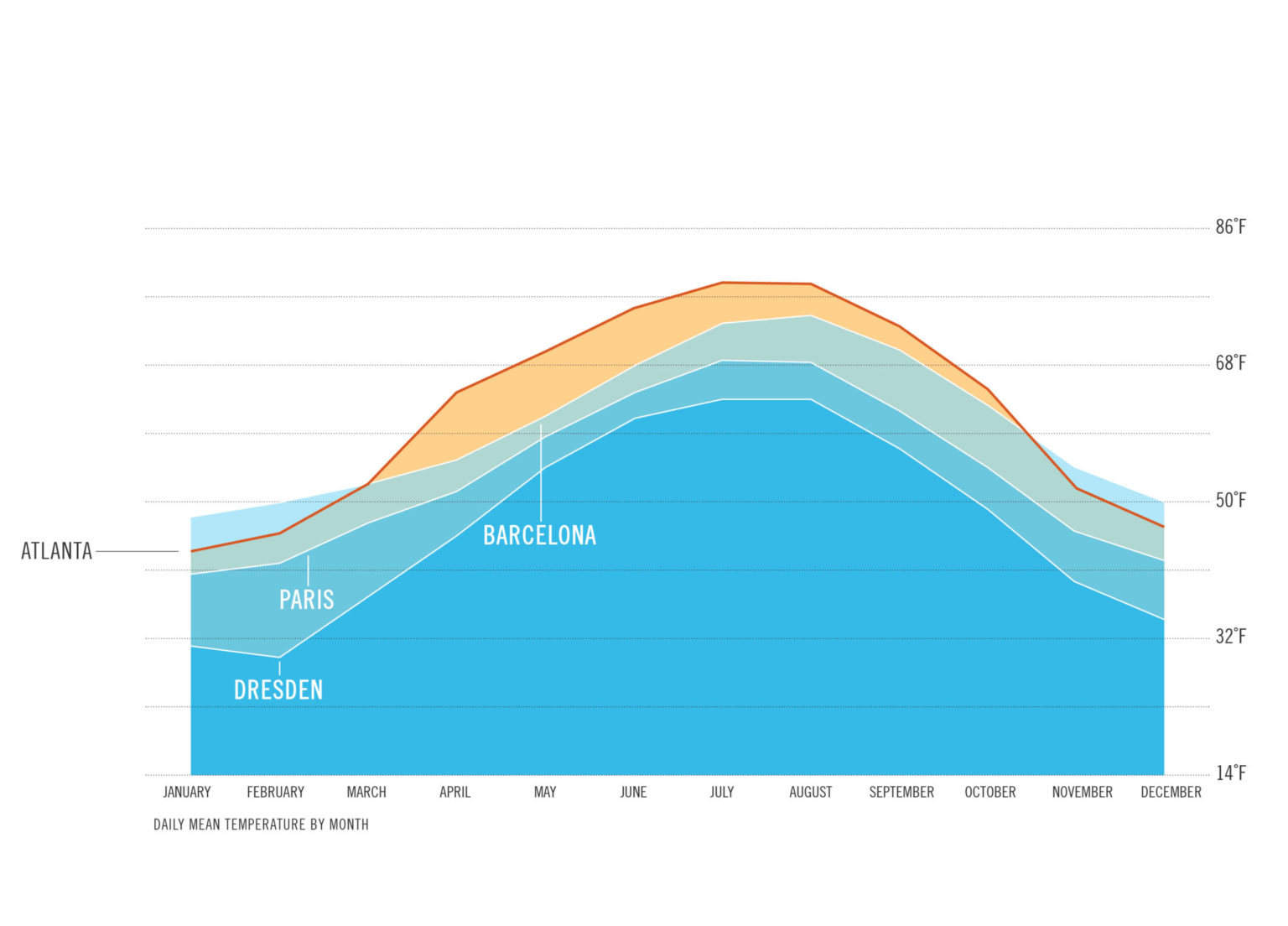

But there were overall issues with green tracks to assess, from electrical isolation to providing good drainage, not to mention the undeniable cost factor. Micah made a case for the ROI and worked to identify how to translate the case studies to his city. Climate would play a role. While Atlanta has relatively large amounts of rainfall, long periods of drought are common. And higher summer temperatures (relative to the European case studies he evaluated) meant he would need deeper soil and irrigation. This and other findings were the basis for his report of recommendations.

Temperature and rainfall comparisons helped shape decisions around the best soil and irrigation for an Atlanta green track design approach.

While transit is integral to the long-term vision of the BeltLine, and the client is seeking additional funding, the focus of the ongoing development has been on trails, parks, and community spaces. So though Micah’s vision hasn’t come to fruition, the research is evergreen—and the pitch remains in his back pocket should the opportunity arise.

In the meantime, he talks up the value of the Innovation Incubator program to prospective hires, emphasizing its role as a differentiator: “It allows you to stay curious and explore like you do when you’re in school,” he says. “It gives [us] the freedom to do this outside the constraints of the marketplace.” Conversely, he reflects, it can make our projects better within those markets.

“It allows you to stay curious and explore like you do when you’re in school. It gives [us] the freedom to do this outside the constraints of the marketplace.”

― MICAH, ON INNOVATION INCUBATOR

Micah and his son

In addition to “Green Tracks,” Micah has completed three other Innovation Incubator projects—reports on therapeutic gardens for children with autism spectrum disorders; the benefits of plants on indoor air quality and occupant health; and designing spaces with plant-species-driven daylight simulation. A life-long learner, he keeps coming back to the well, to dig in to answer questions and bring those lessons back to his work.

More Stories