What’s Old is New Again

Spring 2020

Jens Buch-Dohrmann has a vision for a more sustainable and interesting planet: He believes we should look upon the Earth as one giant material bank.

Jens, an architect at Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects (SHL), calls on the profession to adopt what he calls a global “upcycling design culture”—a mindset that would drastically increase the number of upcycled and recycled building materials in building projects. “It’s a call to action,” he says. “The building industry is responsible for producing around 40% of all CO2 emissions in the world. Using materials that are already there will help alleviate that while also keeping history alive. That’s where it becomes architecturally interesting.”

The timing is right to grow this mindset: Material costs are through the roof, and there’s a growing movement in the EU for a universal tax on CO2 emissions, which would directly affect developers’ bottom line. But what would it take to turn all existing buildings into one material bank?

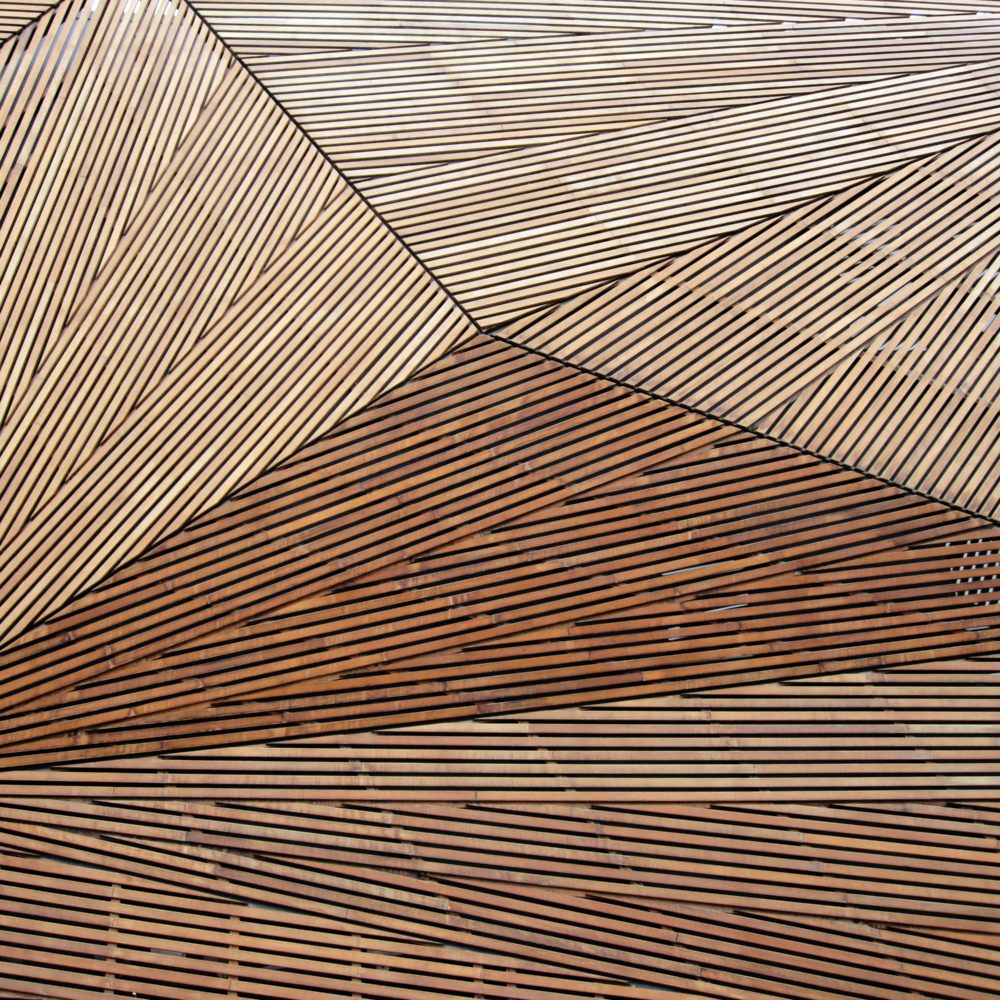

Upcycling design begins when a project has ceased functioning the way it was originally designed—usually because it has reached a certain age. At that point, its various components would be put on the market and sold to the next architect to reuse as part of a new project. When that project reaches its end point, those same materials would again be on the market, creating a circular process that minimizes the creation of new materials.

Jens gives a two-part answer. First, widespread government action and legislation—specifically a climate tax on new materials for builders and purchasers. “People may be interested and want to do the right thing, but in the end, money talks,” he says. “So cost incentives to use what’s already there would be a huge help.”

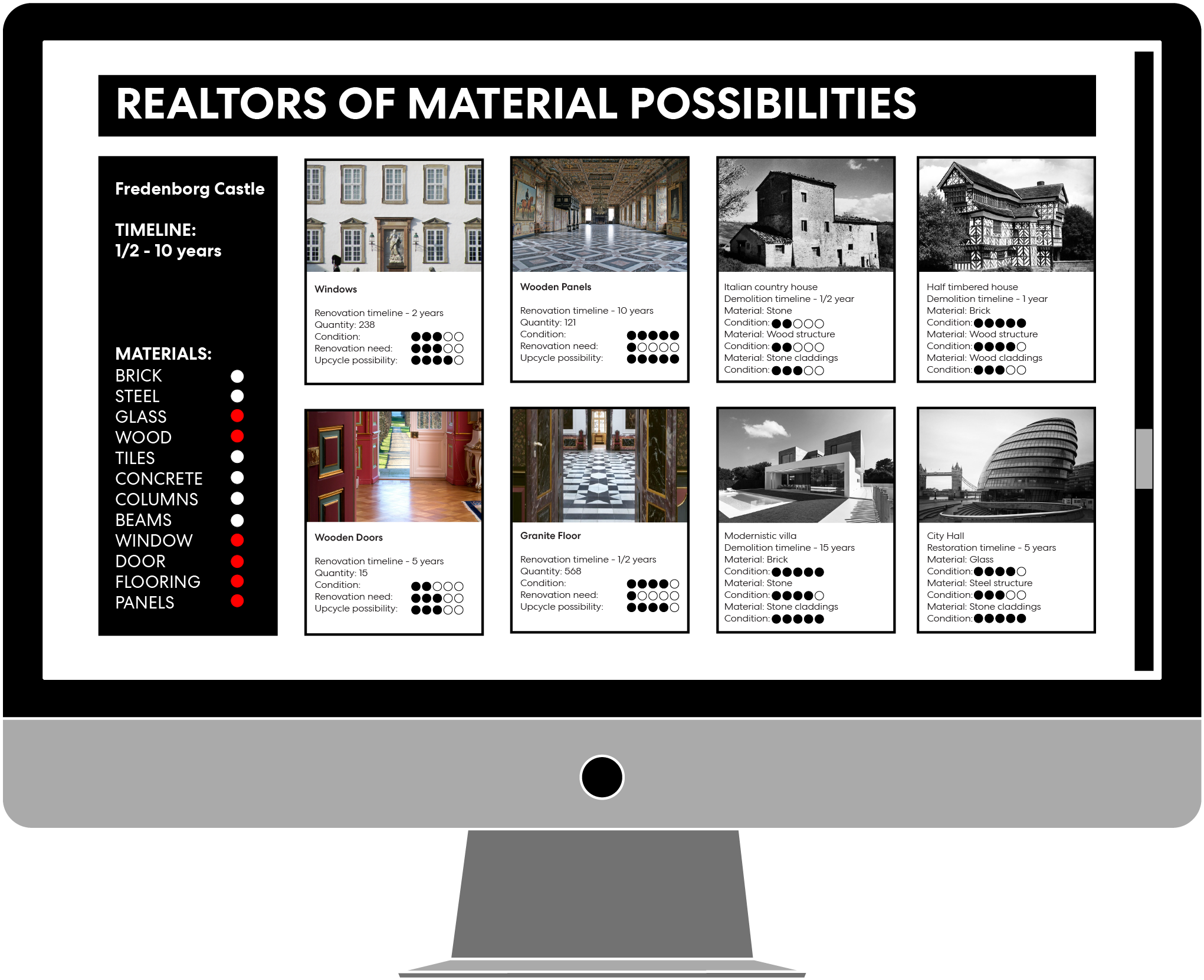

Second, databases of 3D models of building stock in a given city, region, or country. Such databases would allow project teams to find efficient ways to upcycle pre-used building components and materials into new projects. It’s a long game; the databases would be need to be updated as new buildings get constructed and move through their lifecycle. But it’s one Jens’ research shows could pay off. “Fully modeled buildings are relatively new, but in 10 to 30 years, the databases would be substantial and make it easy to know what materials are out there and a fit for a given project,” he says.

There are of course hurdles to achieving this, not the least of which is the fact that buildings aren’t so easily disassembled. Still, Jens is optimistic that the benefits can help architects and their clients see this degree of upcycling as feasible. SHL is already adopting the upcycling design culture mindset for all of its adaptive reuse projects. But in the long run, it will take much more than just one firm for it to successfully alter how we design and build globally.

For Jens, it’s about more than making the building process healthier for Earth. The result will often be more beautiful and purposeful, he argues. “As architects, we are sometimes too focused on achieving something perfect rather than something that gives joy,” he says.

“Incorporating materials with history into new projects adds life to a building. You can retain the human connection with the history of what was already there. Even if you don’t already know the story, seeing something that has been part of so many people’s lives before adds something that is hard to describe in words.”

More Stories